The music of Prokofiev’s juvenile period (although there is really nothing juvenile about it!) spans around c. 1896 – c. 1908. The works he wrote at this time can be broadly categorised into three types: works for solo piano; theatrical works; miscellaneous works. My PhD traces the composer’s development of a distinctive compositional voice using the early and largely unpublished manuscripts as a starting point. In this way I was able to trace a genealogy of his musical style and locate its defining features in early unpublished works. Prokofiev’s juvenilia are characterised by key gestures that make his music immediately recognisable. These childhood works provide us with a snapshot of the composer’s musical thinking. Intriguingly, the source of his later musical syntax, distinctive sound and compositional style are already present in these compositions. These early works are therefore inextricably linked to Prokofiev’s mature musical identity – they remain mostly unpublished, but should not remain unexamined.

Early theatrical works include four operatic experiments (The Giant, On Desert Islands, A Feast in Time of Plague, Undina) that demonstrate a preference for exciting sounds, bright timbres and dramatic moments. They are coloured by a commedia dell’arte quality. These theatrical pieces are essentially piano pieces where Prokofiev experimented with creating and imitating orchestral sounds. Here too we can see the beginnings of the composer’s original voice.

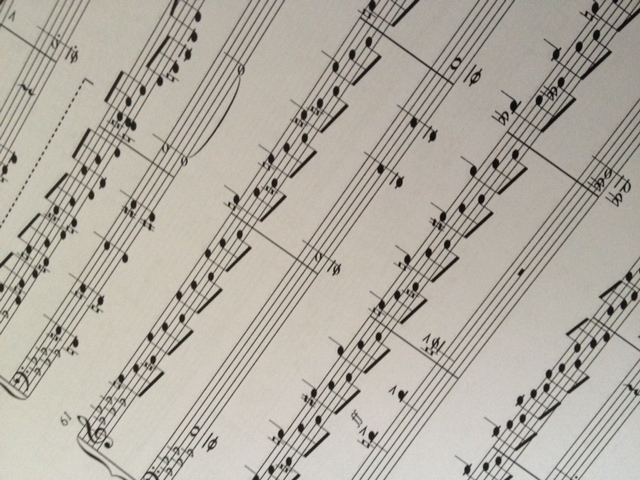

Prokofiev’s precocious flair for the dramatic, characteristic avoidance of conventional harmony and his unerring instinct for surprise can be found in these early works. Other features include frequent changes of tempo and time signature as well as the beginnings of chromaticism. His all-powerful bass line can be seen in different guises – broken chord accompaniment; leaping figures; ostinato; repeated octaves and triads – along with other gestures such as the appoggiatura; the repeated note; alberti-types figures etc.

In this early period Prokofiev uses the piano as a testing ground for ideas he would develop later. Essentially his fingers (technically deficient at this stage) needed to keep up with his ideas. Looking at these early manuscripts really shows how it was a matter of needing to get to the soundscapes he desired with little consideration about how he was to get there. This is one of the most exciting qualities about these early works. He started systematically writing short pieces for piano, grouped in sets of 12, in 1902. These were entitled Little Songs and 5 sets exists (in more or less good order and mostly completed).

These works demonstrate the coming to life of a Prokofievan idiom; the distinctive musical language is unmistakable. The discovery of these early musical fingerprints is what makes such archival work so rewarding. The ‘Little Songs’ emerge as a cohesive group of works characterised by a network of expressive gestures (melodic/harmonic/rhythmic). Another favourite Prokofiev strategy – contrast – is evident here too. His preferred forms are the waltz and the march – hardly surprising then that these remained firm favourites throughout his compositional career.

[I’ve written about this in greater detail here: “The Giant and other creatures: Prokofiev’s childhood compositions”, Three Oranges: the Journal of the Serge Prokofiev Foundation 20 (November 2010), pp. 29-35.]

Leave a Reply